Table of Contents

As a 23-year-old, Ken Pruitt almost died on a survey trip to the Yucatan. It changed his outlook on a career he’d been planning since he was a kid.

“I was lying in a hut in Mexico,” he says, of the location which was miles from medical attention. “I was halfway through a three-year joint degree [in environmental studies and international relations] and I realized I didn’t want to work internationally. I wanted to stay in the U.S.”

But let’s back up. As a kid in Randolph, Pruitt grew up in what he describes as an “outdoorsy” family and it was because of that childhood he was sure he was going to do something with the environment.

“Both my parents were school teachers and we often spent summers camping and hiking [in New Hampshire],” Pruitt explains. “I was always fascinated with nature, wildlife and I really enjoyed the out-of-doors.”

But it was as a teenager that Pruitt cemented his connection to the natural world, turning it into a future career.

“I became more aware of the environmental problems in the U.S. and worldwide,” he says, of his teen years. “I became upset and I wanted to do something about it.”

He even gave a presentation to his local select board in Randolph to get a recycling program off the ground.

“I think by the time I was a senior in high school, I had decided to make a career out of my passion,” he explains. “I especially wanted to do it in other countries because their situation seemed even more dire.”

Pruitt headed off to St. Paul, Minn., where he majored in political science and international studies as an undergraduate.

“I was gearing up for a career working for the State Department or the United Nations or non-profits,” he says. “I was looking at working in underdeveloped countries.”

After college, Pruitt took a year off to work for Ceres, a nonprofit advocacy organization in Boston aimed at creating a more sustainable way of living. Pruitt then went back to graduate school, where he was enrolled in a joint program at Yale’s School of the Environment and School of International Affairs.

Enter that fateful survey in Mexico that changed his life.

Upward career trajectory

After the Yucatan, Pruitt spent three years in Washington, D.C., where he worked for SAIC, a “premier Fortune 500 technology integrator focused on advancing the power of technology and innovation to serve and protect our world,” according to the company’s website. His job was as a consultant for the U.S. Department of Energy and the Environmental Protection Agency.

“As contractors, we weren’t treated as well as the federal employees,” Pruitt says, remembering those days with a laugh. “I did learn a ton. I was in my 20s and when you’re in your 20s, you can try lots of different things. I met my future wife [Teresa] and that was worth the price of admission right there.”

In 1988, the Pruitts moved back to Massachusetts, settling in Watertown. Pruitt took a job as conservation administrator for the Town of Boxford, where he worked as a staff support person for the Conservation Commission, regulating construction near wetlands and waterways.

In 2003, he was hired to be executive director of the non-profit Massachusetts Association of Conservation Commissions, providing education and support to all the state’s conservation commissions.

“It was small, but you’re really in it,” he says, of those five years. “I was chief cook and bottle washer, but it was a great experience.”

From there, Pruitt was recruited to help manage the Environmental League of Massachusetts (ELM), which works to push environmental policy on a statewide level.

“I was there for nine years,” he says. “I think part of it was because I was getting older and it was less about trying to do new things. I also had an increasing knowledge about what I was all about. I liked the scale and ELM’s focus and influence on state government.”

But over time, Pruitt says it became less and less about trying to pass new environmental laws, strengthen the existing ones and making sure other state agencies had adequate budgets. He found himself more focused on fundraising and feeling the pressure of making sure colleagues were able to hold on to their jobs.

“By 2017, I had been running non-profits for 14 years,” he says. “I started realizing that I got into the environmental field because I really cared about nature and the environment. Increasingly, I was facilitating the work other people were doing that I wanted to do. I was growing further and further away from the work I wanted to do.

“It’s one thing to work on influencing legislation, for example, but your organization is just one of several and you’re just one person,” Pruitt continues. “It was really hard to discern your own fingerprint.”

And some of those bills might never pass, Pruitt adds, or it might take years and years.

“I was looking more at climate change and energy,” Pruitt says. “My interests were more and more on how those issues worked in the real world, from cities and towns down to the household level.”

It was then Pruitt spotted a job posting for an energy manager for the Town of Arlington.

“As soon as I saw it, I knew,” he says. “I loved working on that scale and all the pieces of clean energy and the future directly.”

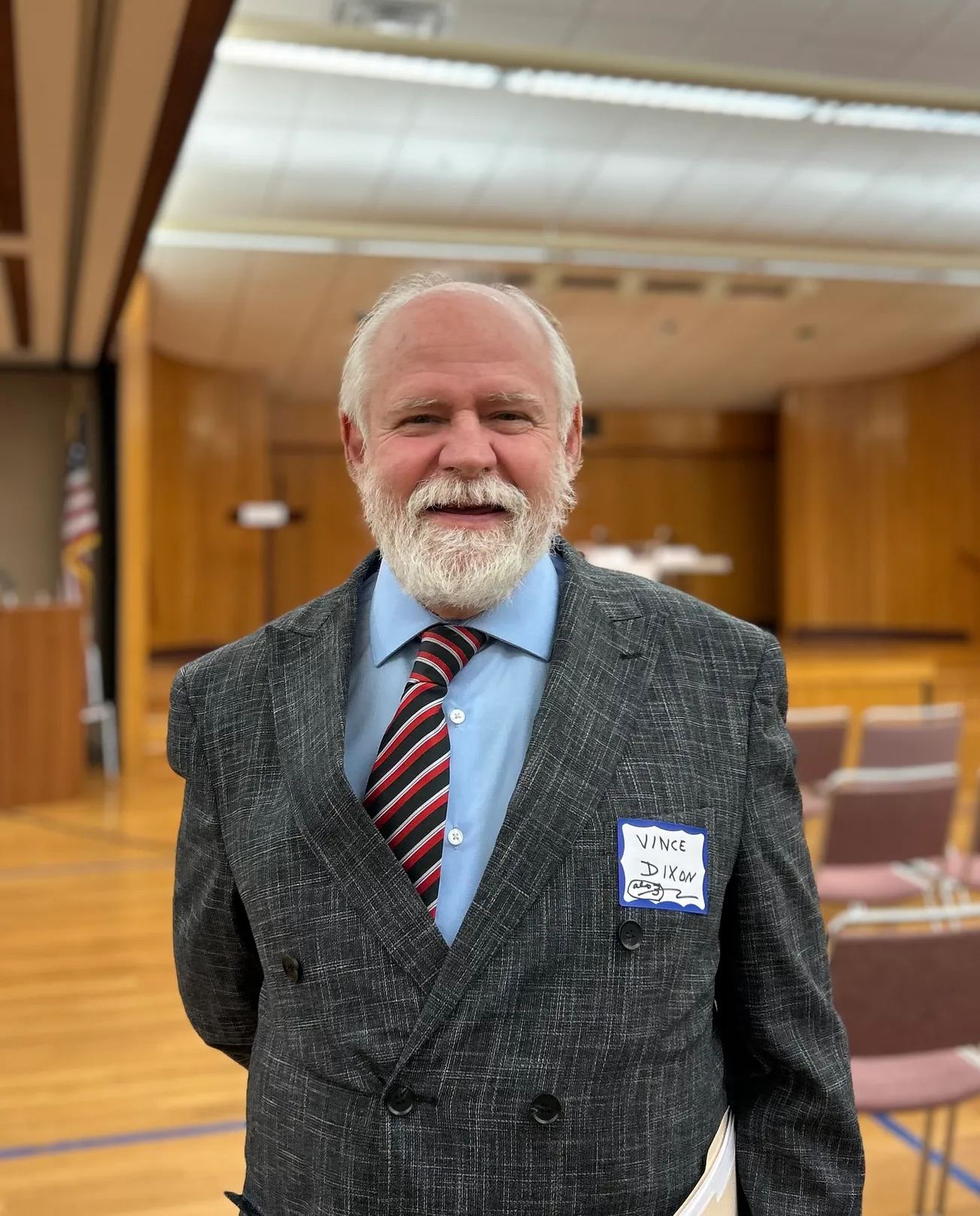

Home to Winchester

Pruitt and his family have lived in Winchester since 2010, with both his kids going through the public school system. He’s also been involved in town activities such as being a Scout leader, among other interests, and been involved in town issues, including becoming a Town Meeting member from Precinct 6 in 2014.

So after four years in Arlington, he saw Winchester was looking for its own sustainability director and felt it was time to move closer to home.

“It was more about the position than the location,” he says, of the job. “Arlington was great, but the role was more reporting to someone else who reported to the town manager. Here, I report directly to the town manager. The ability to get things done is more streamlined. I can go directly to the town manager with any energy and climate ideas.”

Is it weird working and living in the same place?

“Parts of it are strange,” he admits. “I was a member of Sustainable Winchester and I used to volunteer to do all sorts of different things. I brought initiatives to the Select Board as a volunteer and I was involved so that felt a little strange [not doing it].”

But it makes him better at his role.

“The part that I like is that it makes me more effective at my job because I am a long-time resident,” he says.

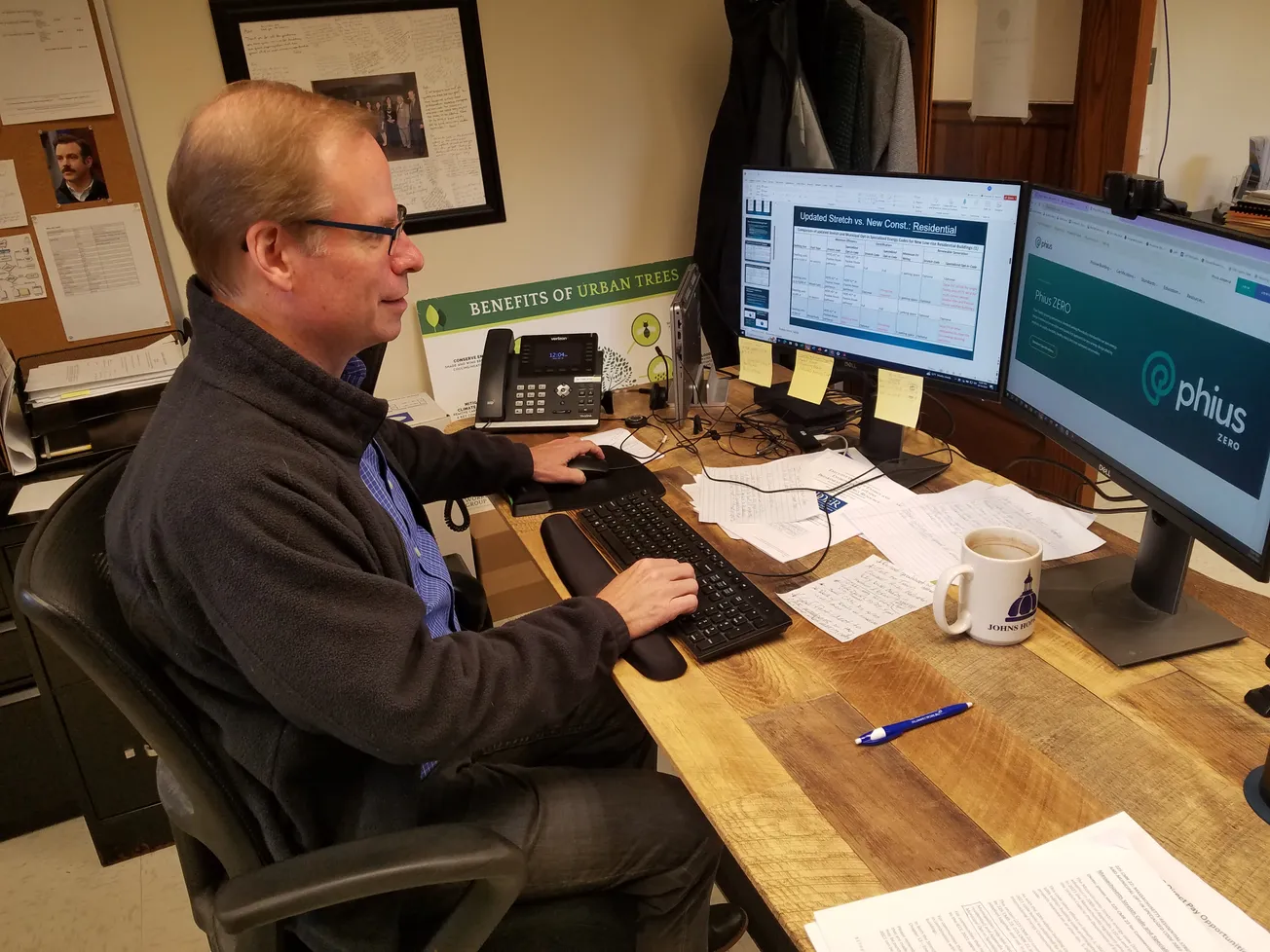

The current job

Months ago, someone asked the Winchester News: What does Ken Pruitt do? When asked that same question, Pruitt laughs.

“The core of what drives my job is implementing the Climate Action Plan, which the town passed in 2020,” Pruitt says. “The plan has about [69] measures that when implemented, will allow Winchester to reduce its carbon pollution 80% by 2050. That was the goal set by the Select Board.”

Pruitt says everything he does in his job is to meet those 69 goals.

Looking at his past work experience — staying in most places about five years before moving — Pruitt jokingly points out his stay at ELM was nine years.

“I’m happy and I’m in a good place,” he says, of being in Winchester. “I think 20 years ago, three years would feel like a lifetime, but now, it feels like I just started this job. It doesn’t feel like it’s been three years at all. I think that’s an indicator that this is where I should be!”

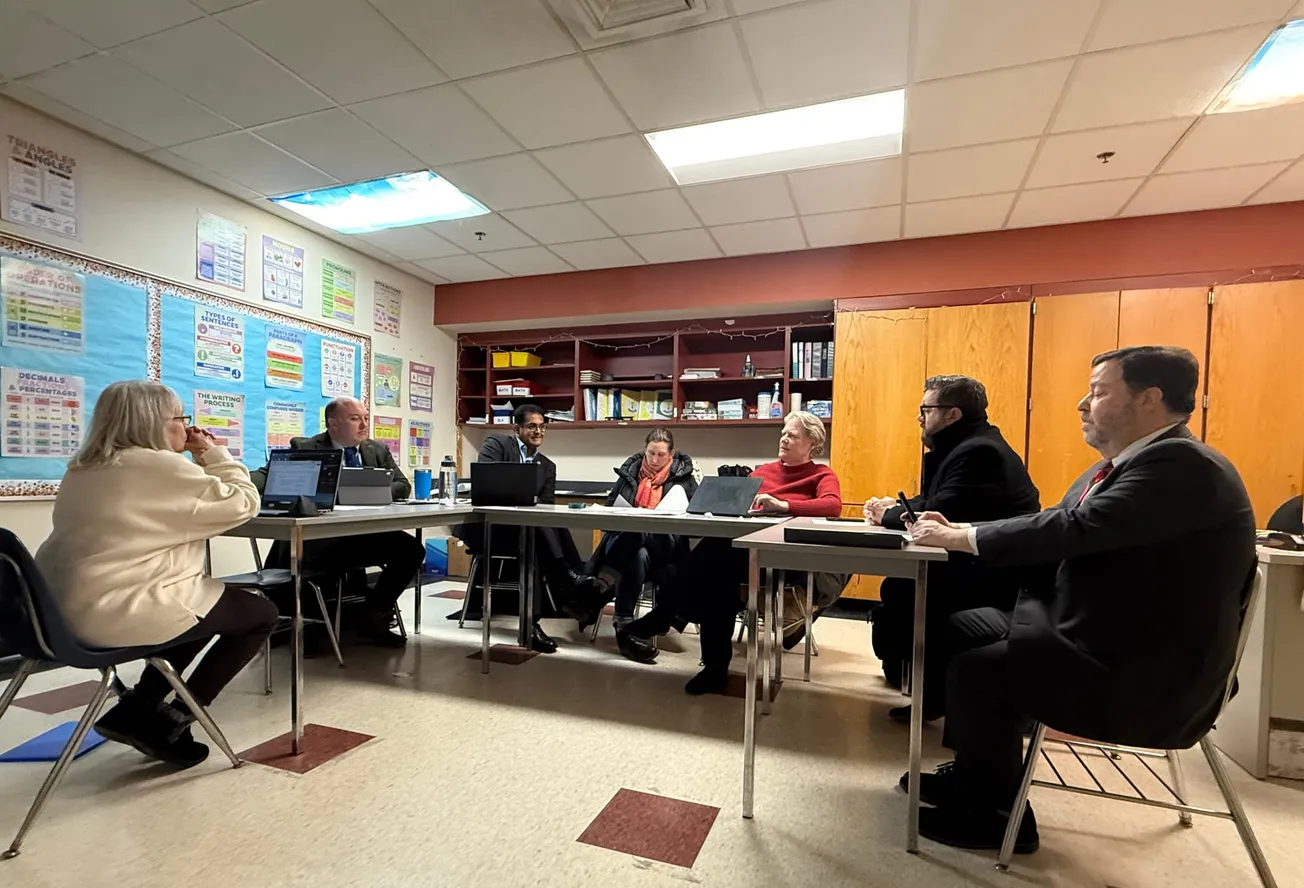

And, he adds, the job allows him to work with some incredible people.

“Between the Climate Action Advisory Committee, the town manager, everyone in the town manager’s office and the other people I work with, I find that I’m taking positive action on the climate,” he says. “It’s a positive, meaningful experience to do this type of work with other people who care about it as much as you do.”

While Pruitt acknowledges some people still think climate change isn’t real, he says the majority of people understand the issue. He says it’s wonderful when they ask questions and want to know what he does and what they can do to help the environment.

“I work in a job where the majority of people are very supportive of what you do and they think it’s important,” Pruitt says. “When you have a measure of success, it’s really gratifying.”