Table of Contents

By Adrien Coakley

What comes to mind when you think of summer? Is it backyard barbecues, going to a carnival or on vacation? Is it going to your local pool, fireworks on the Fourth of July and popsicles?

What about a giant, man eating shark terrorizing a beach town?

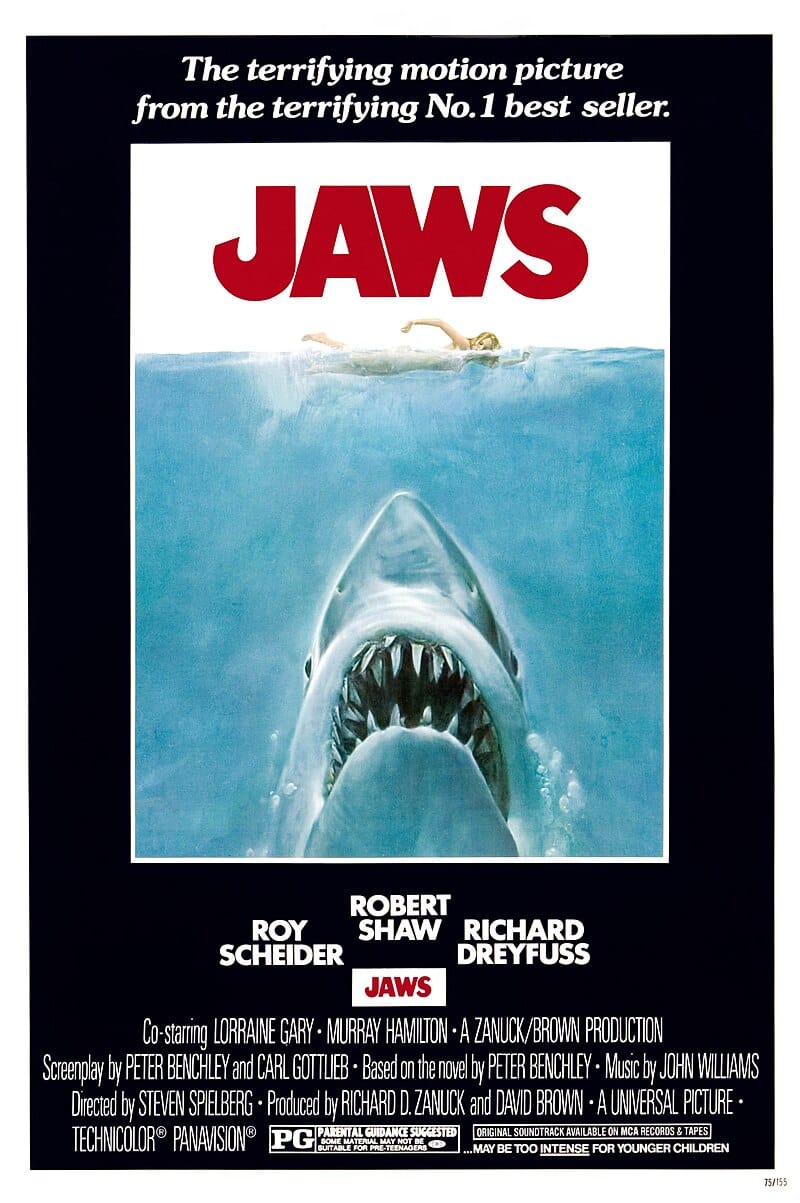

Ever since its debut in 1975, Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws” has been synonymous with the summer season. Often hailed as the first summer blockbuster, the shark epic hit theaters on June 20, 1975, and changed the world forever.

On its 50th anniversary, “Jaws” will be returning to the big screens, from Aug. 29 through Sept. 4, with special IMAX and non-IMAX showings at local theaters such as AMC and Showcase Cinemas.

Locally, events were held on Martha’s Vineyard all summer long, including film screenings and special tours. You can still see the “Jaws at 50: A Deep Dive Exhibit” at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum through Sept. 7, take on the Jaws Escape Room 50th Anniversary Event through Sept. 8 or even just visit the many movie filming locations on the island.

And if you’re planning a trip to the West Coast, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is holding “Jaws: The Exhibition,” from Sept. 14, 2025 through July 26, 2026, the first-ever such exhibit focused on a single film. The museum call sit the “largest mounted exhibition ever for ‘Jaws,’ the Oscar®-winning film from Universal Pictures.”

So, what’s all the fuss over a 50-year-old movie?

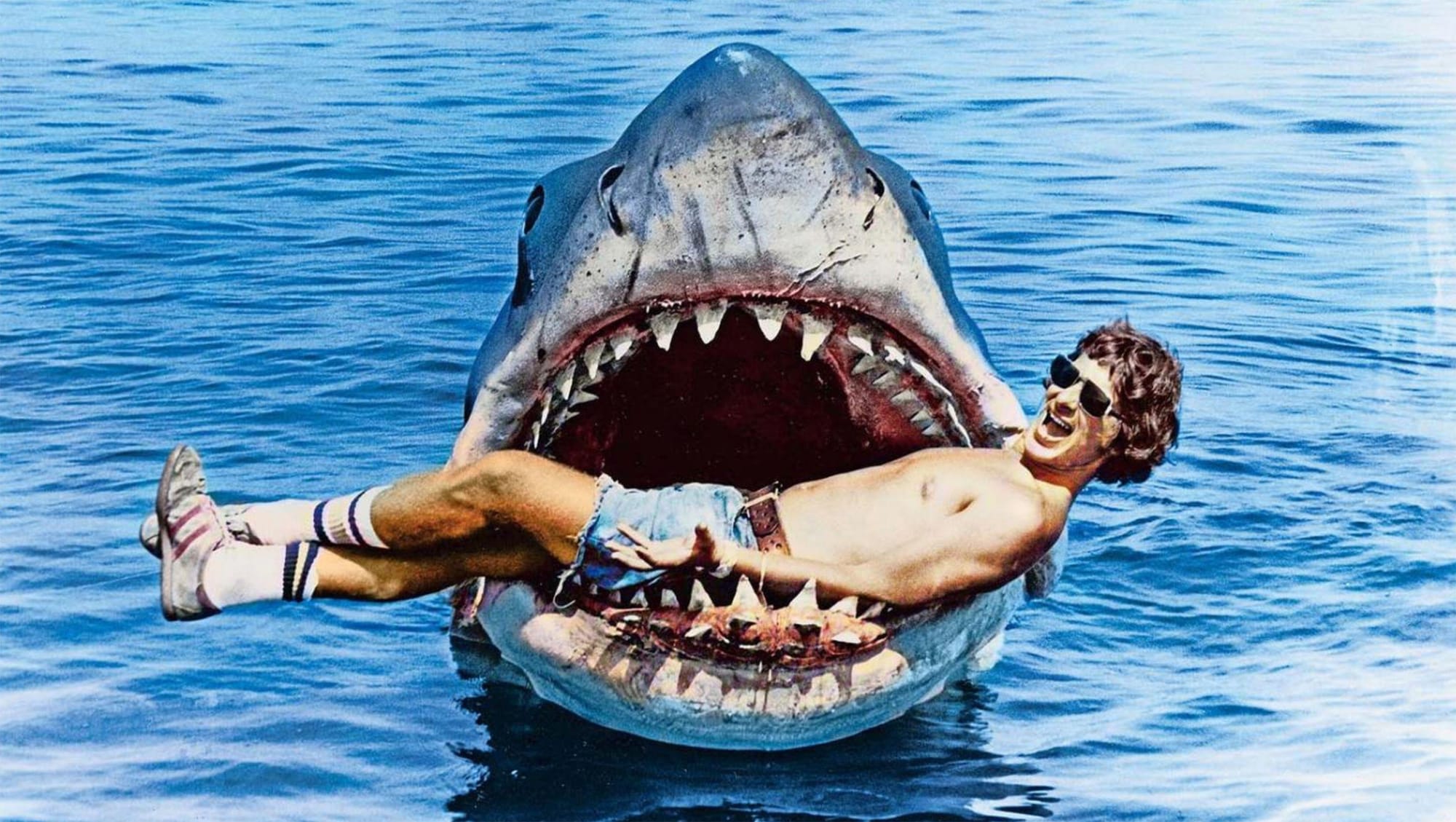

The “Jaws” legacy is undeniable. We all know the iconic John Williams two-note score that follows the shark lurking underwater. We can probably recount Quint’s iconic death in the mouth of the shark as it bites through the Orca. We remember Brody telling the shark to smile as he sets off the tank in its mouth. And of course, we can all quote that off-the-cuff line about how the Orca might need to be a tad bigger.

But, its iconic imagery isn’t the only impact.

“Jaws” has spawned three sequels, none of which would reach the lengths of the original. The poster has been spoofed to death, from t-shirts featuring cats to all sorts of things replacing the famous shark. The theme has been lampooned to signify danger is abound.

“Jaws” is synonymous with the shark movie subgenre, dubbed “sharksploitation,” which varies from Syfy and The Asylum’s famous Sharknado franchise to the Jason Statham starring, book based “The Meg.” Spielberg has even given his seal of approval to 1978’s “Piranha,” directed by Joe Dante.

Once upon a time, the summer was the dumping ground for movies that weren’t expected to do well. “Jaws” was the first to open the doors for studios to release big budget, big spectacle films to kick off the summer season, which would of course lead to films such as 1986’s rip-roaring “Top Gun” and 1994’s Keanu Reeves-led “Speed.”

And, of course, “Jaws” cannot be untangled from the impact it had on sharks.

“Jaws” shifted the public’s perception of sharks into a negative, fearful one. Sharks do not actually attack nearly as often as media shows, with fatal attacks generally reported around 5-6 times a year.

Furthermore, over 500 species of shark are harmless, and only few are ever involved with attacks. According to Shark Stewards, the film led to vendetta killings and more that nearly wiped out all great whites on the West Coast.

“Jaws” has also led to the stereotyping of great whites as mindless killers, which persists even today.

“Jaws” novelist Peter Benchley, before his death, would eventually become a shark conservationist. He wrote many non-fiction novels about the ocean and sharks, among them “Shark Trouble,” which is about how the public’s understanding of marine life can be swayed by the media they consume and how that can lead to negative consequences for both the marine ecosystems and humanity. The book was written to help the public understand the ocean in a post-“Jaws” world.

Benchley’s conservation efforts and education around sharks would lead to the Peter Benchley Ocean Awards being instituted by his widow, Wendy, and David Helvarg. In 2015, a species of lanternshark found off of South America’s pacific coast was named Etmopterus Benchleyi in his honor.

However, the efforts around raising shark awareness hasn’t been entirely hopeless. The Discovery Channel’s Shark Week would be launched in July 1988, originally centering around shark conservation and correcting misconceptions.

Even Spielberg has looked back at the detrimental effects the movie has had on sharks.

In 2022, the director told the BBC’s Island Discs, “To this day, I regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film. I really, truly regret that.”

In New England, and especially Massachusetts, sharks have become a way of life. Thanks to the the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, the seal population has exploded off Cape Cod, bringing with it great whites year after year.

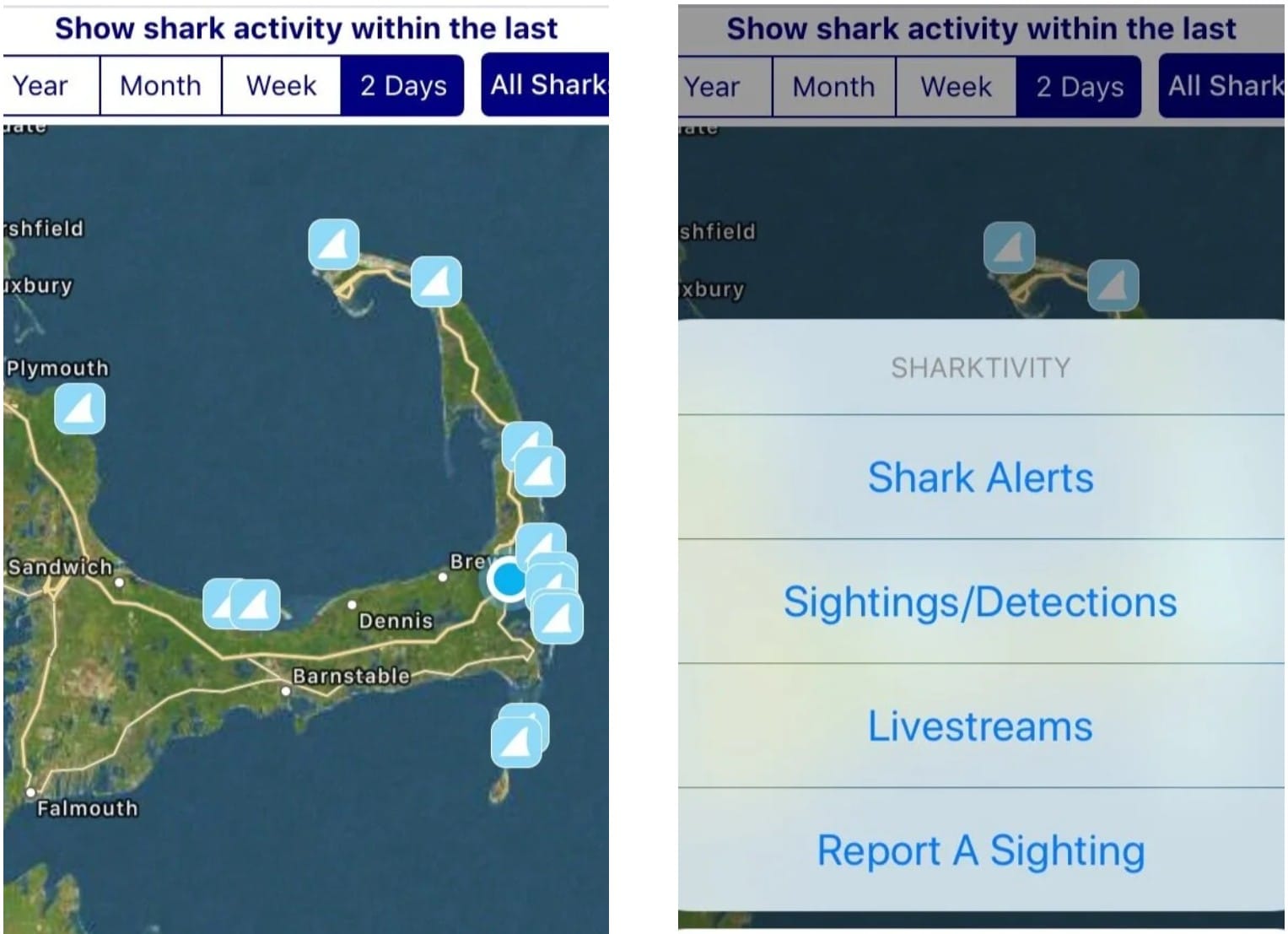

The Atlantic White Shark Conservancy has been tracking the sharks using tagging technology to keep an eye on the predators and study their behavior. The public can also download the Sharktivity app, which not only monitors shark presence in the area, but shows photos of which sharks happen to be swimming and if tagged, can give you their stats and other information.

Just last month, Contender, the largest great white ever tagged in the Atlantic by the research group OCEARCH was found swimming off the coast of Nantucket after several sightings. The shark is 13 feet 9 inches long and weighs 1,653 pounds, according to groups tracking him.

Contender was first tagged off the coast of Georgia in January 2025 and as of July, he was still hanging around off the coast of Massachusetts. Tagged sharks like Contender help researchers with valuable behavior and migration information in the Atlantic.

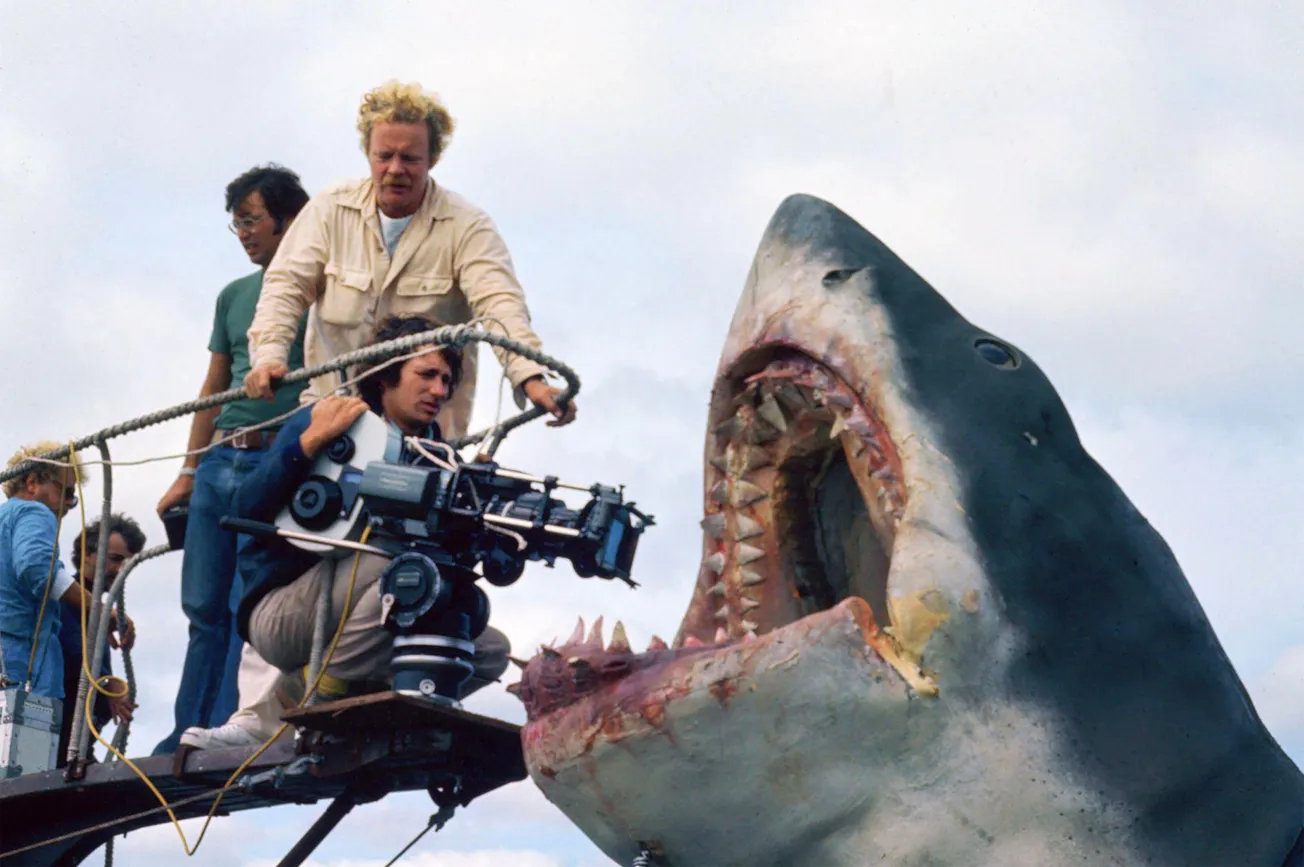

Movie magic

Though its legacy has been both good and bad, there’s no denying that “Jaws” remains a cultural juggernaut, and has cemented a legacy as one of the most iconic films of all time.

“Jaws” first swam onto the scene in 1974, when author Peter Benchley’s novel hit shelves. The novel was born from Benchley’s interest in shark attacks after reading about the exploits of shark fisherman Frank Mundus. The novel received mixed reviews, with critics praising the suspense.

So, how did a novel with mixed reviews turn into one of the biggest cinema cornerstones of all time?

Of course, it started when the film’s producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown both found the novel, read it and considered it the most exciting thing they’d read, and thought it could make a good film. The film rights were then purchased in 1973, before publication, for $175,000 (which, adjusted for inflation, is $1.2 million today).

Though, Spielberg would eventually become synonymous with the killer fish, he wasn’t the first director who came to mind. Zanuck and Brown hired Dick Richards originally. However, Richards would keep calling the shark a whale, and it annoyed the producers so much that they dropped him.

Spielberg wanted the job, having previously done “The Sugarland Express” for the duo. He’d noticed their copy of “Jaws,” and was enthralled after reading it, according to Douglas Brode in his 1995 book, “The Films of Steven Spielberg.” Spielberg eventually landed the job in June of 1973, before Sugarland came out.

Of course, most people know how the production was a disaster from the get-go.

Principal photography began on May 2, 1974, in Martha’s Vineyard. The location had been chosen due to the surrounding ocean’s bottom never dropping beneath 35 feet for 12 miles out from shore, which would ensure the sharks to operate outside of the sight of land, according to the featurette “A Look Inside Jaws” on the film’s 2005 DVD release for its 30th anniversary.

One of its notable problems was filming on the open seas. “Jaws” was the first major film to shoot on the open ocean, according to actor Richard Dreyfuss. In 2024 in USA Today, he recounted the cast and crew would have to wait for any sailboats to pass by before they could shoot, and the shoot involved lots of waiting.

Of course, the most infamous problem on set was the film’s fourth star: the animatronic shark. Initially, the producers wanted to train a real great white shark for the film. Seeing as this is impossible, it was Spielberg’s idea to have robotic sharks built, to the tune of $250,000 each, which would be about $1.6 million today.

Bruce, as it was nicknamed (after Spielberg’s lawyer, Bruce Ramer, a nod to their friendship), was actually three separate animatronics, none of which ever functioned properly due to the fact that “Jaws” was filmed in saltwater, which wreaked havoc on the internal machinery. The sharks also suffered from fractures.

Having been tested in freshwater, the animatronic sharks initially worked. Out on the ocean, it was a different story. For example, one of the sharks, on a test run, ended up sinking to the bottom of the sea.

The robotic sharks were also covered in a “non-absorbent” foam skin, which ended up absorbing liquids and causing the sharks to balloon. The sea-sled shark, which was a full body prop shark with no belly towed along a 300 foot line, would often get tangled in seaweed.

The shark troubles eventually led Spielberg to take the Hitchcock approach, to not show the shark, but leave it up to the viewer’s imagination.

Speaking of star troubles, “Jaws” had plenty of that around. Robert Shaw, who played Captain Quint, often drank on set, which would lead to him poking fun at Dreyfuss, and the two despised each other. Shaw’s alcoholism also troubled Spielberg, who often had to scrap and re-shoot scenes due to Shaw’s lines either being forgotten or his words slurred.

Rare Interview: Robert Shaw discussing his relationships with Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss

by u/Kootnybehr in Jaws

The actors were often seasick, and were once atop the film’s famous boat, The Orca, when it began to sink. The film had 12-hour days, but due to weather conditions and unexpected delays, such as unwanted sailboats, only four hours ended up with any kind of film in the canister.

According to a 1975 Time article, writer Carl Gottlieb was nearly decapitated due to the boat’s propellers, and Dreyfuss nearly got stuck in the cage used for Hooper’s dive.

To top it all off, the script was often being rewritten on set, the budget ballooned from the estimated $4 million ($25.6 million now) to $9 million ($59.8 million today), $3 million, or $20 million of today’s money, of which had to go to effects due to the sharks’ many issues.

The shoot had a schedule of only 55 days, but due to the many problems, principal photography wrapped on Oct. 6, 1974. The total amount of days ended up at 159.

The production was so troubled, in fact, that disgruntled crew nicknamed the film 'Flaws', according to Joseph McBride’s 1999 book “Steven Spielberg: A Biography.”

On June 20, 1975, “Jaws” would finally make it to the silver screen in 464 screens, of which 409 were in America. This, alongside Universal’s TV campaign, resulted in an unheard-of release strategy.

The film was a major success, and its success caused the film to slowly open in more and more theaters, hitting over 950 theaters by that August. Overseas release followed the same pattern, with the film initially hitting 100 theaters in Britain.

“Jaws” opened with a $7 million weekend, or $42 million today, setting the highest grossing record of 1975. It would go on to be the first movie to earn $100 million in American and Canadian box office gross. It would go earn $123 million in its initial run.

Re-releases in 1976 and 1979 brought it to $133.4 million, entering overseas in December of 1975. On Jan. 11, 1976, the film claimed the record of highest worldwide gross from “The Godfather,” beating it by $1 million.

Re-releases since, including in June 2015 for its 40th and September 2022, brought its total to a staggering $478 million. Adjusted for inflation, it has almost earned $2 billion as of 2011 prices.

Critics were enamored by the shark thriller, including Roger Ebert, who gave it four stars.

“Jaws” would go on to be nominated for four Academy Awards, taking home the statues for Best Film Editing, Best Sound and Best Original Score. It lost its nomination for Best Picture to “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

— Winchester News editor and reporter Nell Escobar Coakley contributed to this report.