Table of Contents

In a significant move the last week of July, the Massachusetts Senate overwhelmingly approved legislation requiring all public schools to enact a “bell-to-bell” ban on cell phones and similar devices during the school day.

The bill, which passed by a 38-2 vote, prohibits students attending public schools in Massachusetts from accessing personal electronic devices, from the moment school begins until dismissal, including during lunch and between classes.

“It’s an issue that’s been coming up quite quickly,” said Paul Albright, director of communication for Sen. Jason Lewis. “There’s issues with academic performance, social skills, and emotional development.”

Lewis agreed.

“Numerous studies have shown the many benefits to student learning and well-being by removing cell phones from their educational environment,” he said.

Public opinion aligns with what scientific studies have shown. While developing the bill, Lewis and other legislators surveyed students, parents, teachers, school administrators and other advocates and experts. The result, they found, was the public believes students don’t need to have personal devices while they are in school and that cell phones distract from learning, hurt students’ social skills, and harm students’ mental health.

Outside of the educational environment, cell phones are impairing the ability for students to develop their social skills with other students, explained Albright. By removing them, he said, it aids students in creating meaningful relationships with their peers.

Lewis said in order to get the benefits of improved academic learning, improved socializing among students and social skills, and mental health and wellbeing, it is critical the ban is for the full school day.

“There’s a lot of research that shows limited cell phone bans are not enough to reduce the harm to students,” he said. “You really need to cover the full school day to get the benefits.”

There will be three exceptions for certain students who rely on their cell phones for learning.

“If the student has a disability that requires the use of a personal electronic device, then they will be allowed to keep their device during the day,” Lewis said, of the first exception. “Similarly, if the student has a medical reason for having a device on them, and their doctor has signed off on it, then the student will also be able to keep their device. The third exception is if a student has to go off campus to go to another educational program such as an early college program or vocational program.”

A major concern for students and parents is student safety and the ability for students to connect with their parents during the school day. Lewis clarified all schools need to provide a way for parents to contact their students during the school day if there is a good reason to do so.

It is a big adjustment for schools, Albright added, which is why the bill has left a lot to local control.

“[Districts] are allowed to decide what restrictions are, which exceptions are best for them, and the bill would also require the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) to solicit public input, and so they would be providing guidance recommendations and a model policy,” he explained.

Massachusetts movement

There are existing cell phone limitations/bans already in place in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Association of School Superintendents estimates about 80% of school districts have some policy on cell phones.

However, Lewis said the new law would require some districts to be more comprehensive, and stronger.

If passed, Massachusetts will also not be the first state to enact a bell-to-bell ban.

“We are a late mover, there are already about half of the states that have some sort of policies statewide that restrict or prohibit the use of cell phones in use,” explained Lewis.

More than 30 states, including Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and New York, have laws banning or limiting student cell phone usage during the school day. Florida led the charge in 2023, and New York’s “bell-to-bell” phone-free law took effect in the 2025–26 school year, starting Sept. 2.

The prohibitions are meant to minimize distractions, improve mental health and academic performance, and public support is gaining momentum, as favorable reports and widening advocacy propel further adoption across the country.

Albright said the bill that was passed by the Senate is very similar and partially modeled after the other statewide bills that banned cell phone use during school hours.

There is still a long road until the bill is passed into law. Albright explained that after the Senate passed the bill with a bipartisan vote of 38 to 2, the bill moved over to the House, which can either choose to act on that bill or alternatively, create a bill of its own.

The current Senate bill already has support from Gov. Maura Healey and the two largest teacher unions.

If the Legislature passes the bill into law during its next session, it won’t go into effect until the 2026-27 academic year. And it will still be up to individual school districts to iron out some of the finer details.

Albright said in addition, the bill requires that DESE report back to Legislature on the impacts of these restrictions by the end of 2027.

Winchester High School perspective

As Massachusetts lawmakers consider banning student access to cell phones, Winchester High School is debating how policies would be implemented in its own community.

In August, Principal Dennis Mahoney spoke about the issue, citing both the benefits and challenges of restricting phones in class.

For years, WHS allowed teachers to set their own rules around cell phones.

“Your math teacher might not have allowed cell phones at all … but your English teacher might allow them as a learning tool,” Mahoney explained.

This approach, he said, gave students a chance to learn when phone use was appropriate, but also when it was inappropriate.

But as phones became a bigger classroom distraction, some teachers pushed for a unified policy. Mahoney resisted a one-size-fits-all rule, pointing out that with 1,400 students and 200 staff, those types of rules rarely work, as classrooms function differently. This was the system up until this year.

Dr. Elizabeth Often, Winchester Public Schools director of mathematics for grades 6 to 12, echoed that sentiment.

“People can get distracted by really any electronic device that can access the internet,” she explained. “Whether it is your cell phone, watch, laptop, you have to have discipline and the decision to not access that when you need to be focused on something else. That is really hard and the way the device is designed makes it even harder.”

In Often’s classroom, her expectations are that phones need to be in the student’s bag unless told otherwise. But there are classrooms which allow students to keep their cell phones on their person.

Often said although teacher autonomy is very important, it becomes difficult to transition from one policy to another.

“When you have expectations that differ from classroom to classroom,” Often said, “it becomes very hard for students and teachers and school leaders to back up a teacher who doesn’t allow cell phones to be used ever, when six other teachers on the same floor have differing policies.”

Some teachers may not need to make significant adjustments to their cell phone policies since they are already stringent.

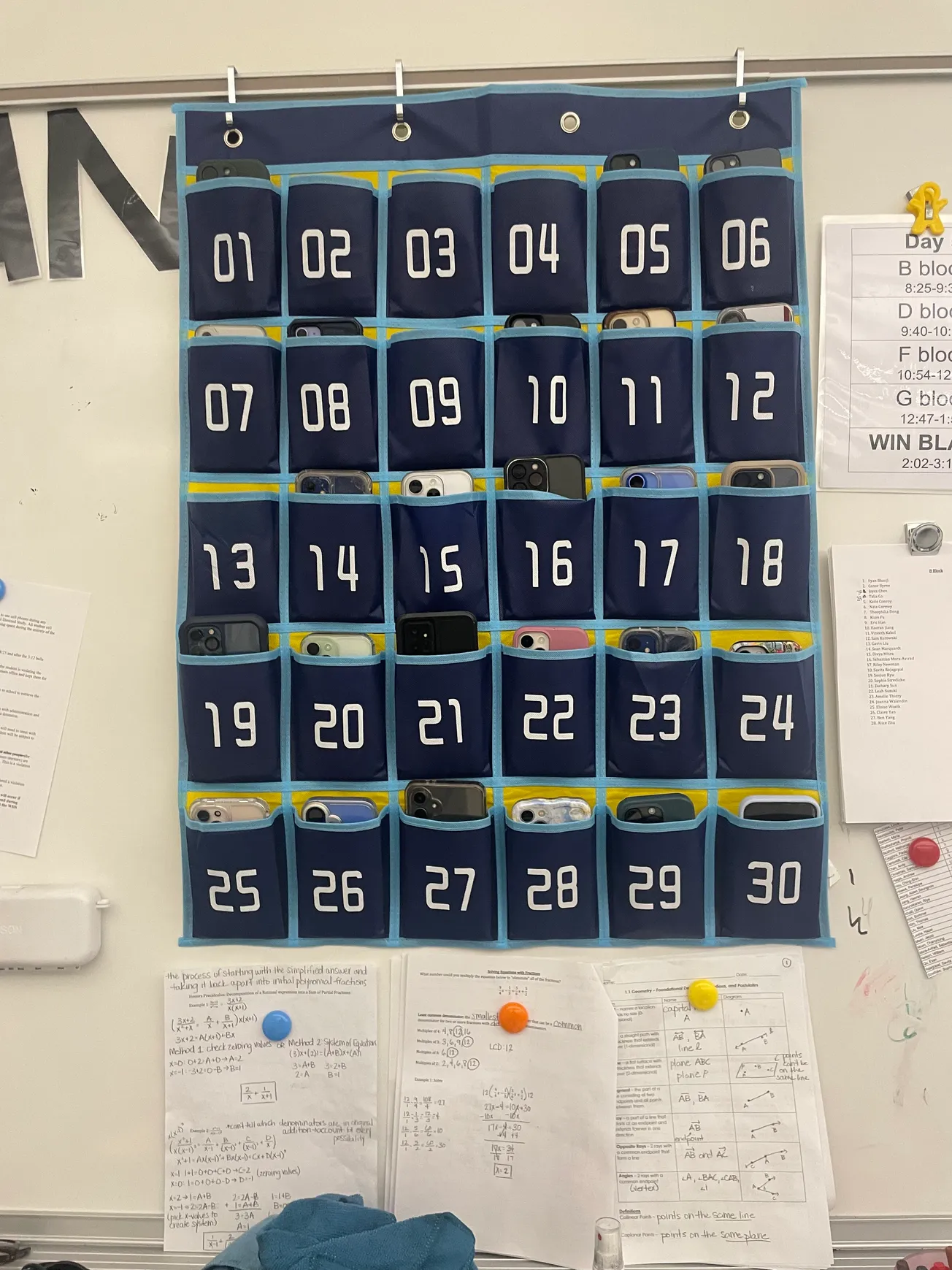

Michelle White, a biology teacher at Winchester High School, said in her classroom, students are expected to place their devices in the “phone locker” for the entirety of the class, which is similar to the system that will be used with bell-to-bell.

White’s experience with phones is similar to Often’s as she has also seen how students are distracted.

“Students often disengage from each other, struggle to communicate face-to-face, and even default to emailing adults instead of having direct conversations,” said White. “It impacts their confidence, relationships, and ability to focus on learning.”

Lewis also argued phones hinder social interaction. Mahoney, however, said that doesn’t fully reflect reality.

“When you’re in the cafeteria, you see kids on their cell phones, but sometimes they’re just taking a break, or they’re introverts and just need a break socially,” he said. “And plenty of kids are interacting, even while using their phones.”

Mahoney admitted there are times when you can walk into the cafeteria and see a dozen kids by themselves on their personal devices. But, he argued, they are making a conscious choice to kind of downshift and have a moment to themselves.

He added that with a unique open-campus lunch policy, much of Winchester’s student body interacts off campus as well.

“When you’re walking to Toscano’s or driving to Chick-fil-A, there’s plenty of conversation going on,” he said.

What are students saying?

Winchester High School students feel cell phones are not as harmful as people make them out to be.

“Perhaps there are kids who decide to use their phone in class, play games instead of learning, but that’s their own choice and these actions have consequences. Maybe on the day of the test they aren’t prepared and don’t do well,” explained one Winchester High School student, who asked not to be named.

Socially, students at Winchester High School say they are a medium for interaction just like anything else.

“A lot of the time, phones are a way for people to connect and socialize,” said another student. “Sometimes kids who have never even talked to each other interact because they have a shared game they like to play. It’s just like board games, people interact because they have similar interests.”

Many students had a similar conclusion: phones are never going to disappear and are going to continue to be a bigger part of our lives. Instead of banning phones, students say it is more important to find a way to incorporate them into learning and socializing.

A recent school survey revealed a sharp divide: most students said phones don’t hurt academics or social life, while staff largely disagreed.

Mahoney wasn’t surprised.

“Students are happy with the status quo … they don’t know how much better it could be without distractions,” he said.

Staff, the principal noted, see the potential for deeper learning without phones, as they have gone through school without personal electronic devices.

The most “interesting data,” Mahoney added, came from parents.

“We mostly expected that the students would be pushing for the status quo and the teachers pushing for change, and that these two groups would not be in lockstep,” he said. “But interestingly, the parents were split, some strongly supported a ban, some opposed, and many fell in the middle.”

What parents are thinking

Kathryn O’Connor, a parent of children attending Winchester Public Schools, explained her concern began when she noticed the amount of smart devices young children had.

“It just didn’t feel right,” she explained. “Kids were using them at recess, sometimes to get online and even showing inappropriate content to classmates. That’s not what school should be about.”

For O’Connor, these restrictions are a way to protect what school is meant to be.

“We wanted school to be a place for kids to figure out friendships, solve problems, and resolve conflicts face-to-face, without screens in the way,” she said. “This policy feels like a win because it gives them that chance.”

O’Connor and another parent, Erica Walsh, decided to form Let Kids Be Kids, an organization that advocates for delayed access to personal devices and phone-free school days. As more data around how smartphones affect children and adolescent mental health becomes available, Let Kids Be Kids aims to let parents know that if they don’t get their child a smart phone, they won’t be alone.

In addition, O’Connor highlights the importance of independence for children. In her opinion, children require space to sort things out for themselves, from navigating friendships or riding their bikes into town.

“Phones can get in the way of engaging in real life,” she said. “Giving children more freedom to experience the world builds the kind of confidence and maturity they’ll carry into adulthood.”

Instead of adopting the increasingly popular “bell-to-bell” ban, Winchester chose a compromise: class-to-class. Phones are banned during lessons, but students can still use them in hallways between classes and the cafeteria.

“We looked at the data for the students, staff and parents, all of the data we do respect,” explained Mahoney. “We felt that a nice middle ground or at least an entry level to more limitations would be class-to-class.”

Mahoney argued a strict ban wouldn’t fit Winchester’s culture. Winchester High School is one of the few schools in the entire area that has an open campus for junior and seniors for lunch. He said if the district were going to follow the way the state is laying out a ban, it would mean that if you’re going out to lunch, if you’re walking down to Starbucks, if you’re driving over to Chick-fil-A, you still can’t have your cell phone.

“It’s no cell phones during the school day. And that culture doesn’t fit in the culture of Winchester High School,” Mahoney said. “People like to talk about data and the data is accurate. There’s no arguing with the data, but the data doesn’t always fit the culture or narrative of your school.”

If Massachusetts mandates a full ban, however, Winchester will need to rethink enforcement.

Mahoney said that, for now, students who break rules may have their phones collected and returned only to a parent.

“It’s an inconvenience for the home, the student, and the school,” Mahoney said, but the goal is to encourage better decisions rather than rely solely on punishment.

School Committee weighs in

While Mahoney viewed the new phone policy as a school culture compromise, the discussion has also extended to the School Committee.

In August, the committee voted 4 to 1 to switch from a teacher autonomous system where teachers can decide how cell phones will be used in their own classrooms to a class-to-class system, where students must leave their devices in wall-mounted phone holders during class time.

Although the majority agreed this change would be a good first step, not everyone agreed.

Committee member Stephanie Mnayarji cast the only dissenting vote, but her concern was not that the new policy was too restrictive, rather that the policy did not go far enough to cover more personal devices.

“AirPods, smartwatches, whatever new technology comes next, it’s all part of the same distraction,” she said.

To Mnayarji, the bigger priority is creating a consistent, distraction-free environment across the whole school day.

The School Committee was also presented with the survey data conducted at the high school, which highlighted the disconnect between teachers, who favored a stronger policy, and students who favor to keep the status quo.

Mnayarji wasn’t surprised.

“Of course students feel targeted, it’s their phones being addressed,” she said, adding the committee has to analyze those views with evidence from other states.

While Massachusetts legislators are pushing for their own “bell-to-bell” legislation, Mnayarji said this is Winchester’s opportunity to learn from existing policies in places like New York, Florida, and California.

For this upcoming fall, the high school will move forward with the classroom-to-classroom cellphone policy. However, Mnayarji emphasized this is just the beginning of what may turn out to be a multi-phase procedure. She feels measuring the success of this new system will require looking much deeper than just test scores or grades.

“I’d love to see how this affects students’ mental health, too,” she said, acknowledging such objectives are much harder to quantify.

“This isn’t just about kids,” Mnayarji continued. “Screens are a challenge for all of us. We’re preparing students to step into workplaces and colleges where phone-free spaces already exist. Learning how to set those boundaries now is part of preparing them for real life.”