Table of Contents

If you ask seemingly anyone, particularly students, involved in the McCall Middle School portfolio assessment pilot program what they think, they will tell you – it’s better than MCAS.

“You know, as many years as I’ve been doing it, I cannot recall one essay I’ve written on MCAS that has left me with something that I think is as meaningful as any of these projects,” said Emily, a Winchester High School freshman. “I think all of the messages behind these projects are much more meaningful than reading an essay and or reading a story and then writing an essay based off of it while I sit down to take a test for four hours.”

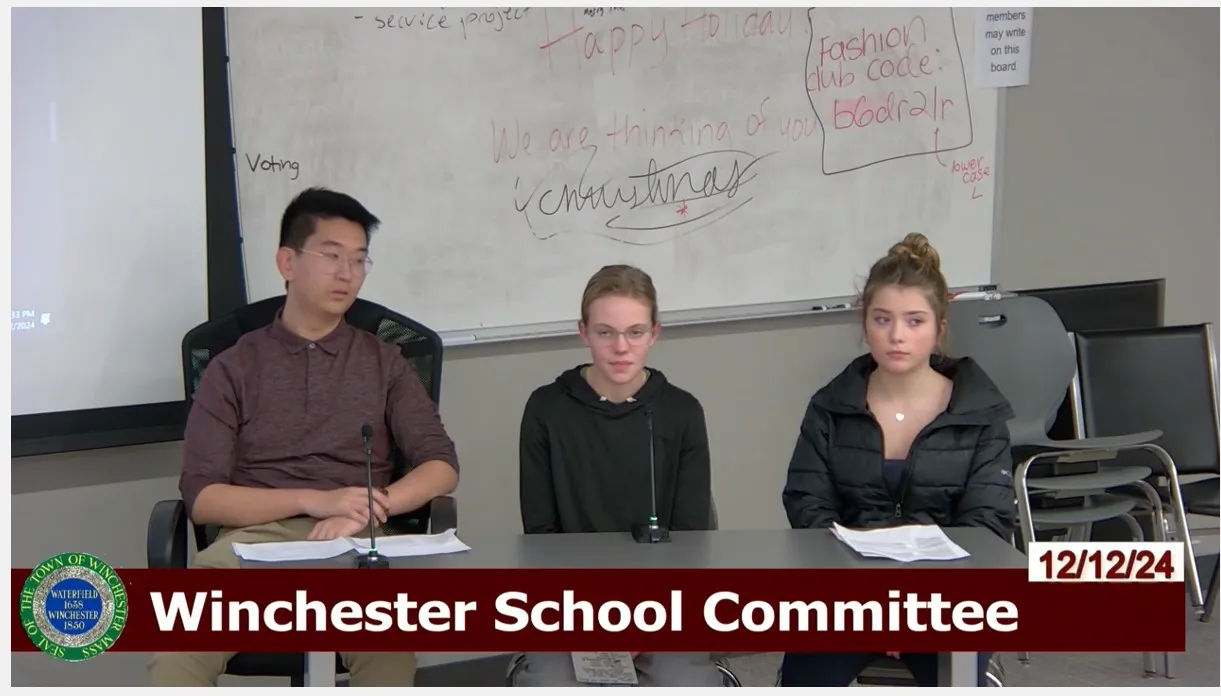

As an eighth-grader, Emily participated in the first year of the portfolio pilot program. She, along with classmates Josh and Olivia, shared their reflections with the School Committee during a recent meeting at the behest of the McCall eighth-grade English Team.

Winchester is one of eight public school districts that have joined the Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessments (MCIEA).

Carolyn Plosky, director of English for grades 6-12 said the district’s work with MCIEA is to “design and implement and assess quality assessment materials that speak to real world tasks that we ask our students to do and this is really the opposite of what MCAS is asking our students to do.”

Plosky said about a year and a half ago, MCIEA decided to formulate a portfolio pilot by asking groups of teachers to design and implement performance assessments that would demonstrate the exact standards that MCAS requires of students. And McCall was one of four schools that volunteered to take part.

How does it work?

The concept is simple, while MCAS is a standardized test given to kids in grades 3-8 and 10 (and sometimes 9), a portfolio, explained English teacher Kate Thompson, is a collection of a student’s work that shows their growth and development over time.

Thompson said the school started the process by setting priority standards students must reach.

“These are things that we really feel like students need to have a grasp on in order to not only show mastery for the grade level, but also to show mastery in terms of just real-world application of their skills.”

But what does that mean?

The English team chose three student projects to focus on: student written editorial/opinion pieces, an “I believe” essay and an art/activism project, said teacher Claire Powell.

Former eighth-grader Olivia said learning to write an editorial not only strengthened her argumentative skills, but it taught her persuasive-style writing, which she “pretty much did not know how to do.” And she got to put those skills to the test when students were invited to enter their editorials in the New York Times Student Editorial Contest.

“I think I can speak for all the other students when I say that doing this assignment really helped us to look deeper into our writing and analyze our skills a little more and overall grow as writers,” Olivia said.

Equally important, Olivia noted, was the student’s ability to choose what they wanted to write about rather than working from a prompt or specific book.

“I think students really got a lot more out of writing about their personal beliefs, because when you’re writing about something you care about, you can showcase your skills and your strengths, and you also feel more inspired and you work harder,” she said. “The editorials … I think, were really our best work, and I think it also helped to show students how much meaning and importance writing could have when it’s not just about like a book or something stereotypical. I think it inspired students to love writing a lot more.”

Emily and Josh agreed the freedom of choosing your own essay topic and art project idea had a huge impact on them.

Josh said for the “I believe” essay, they first read a number of essays and deconstructed them, brainstormed core beliefs then put it together in an essay. It was, he said, one of his favorite assignments.

“I really enjoyed this activity for two main reasons, the self-reflection aspect and the aspect of freedom,” he said.

Josh added by giving students time to discuss core beliefs, they gained a deeper understanding of themselves and having the freedom of choosing their own topics motivated them to work harder.

“Because we felt a deeper, more personal understanding and connection to our work,” he said.

The art project was the conclusion to the social justice unit, and similarly gave students the freedom to choose which area of social justice they wanted to represent.

“I think art is very powerful and often overlooked in English curriculums,” said Emily. “It’s a very powerful way to reflect on ourselves, but also the unit that we’re doing, and I think it works perfectly with the social justice unit.”

Students were given the chance to research artists and activists, review their work and discuss it in class, then created their own pieces of art to represent one of their beliefs about social justice.

“This project allowed me to go and research myself, research the kind of activism I was interested in, which helped me understand the kind of things that I believe about social justice,” she explained.

In the end, Emily said the artwork was as much a reflection of the artist as it was social justice, making it even more personal and meaningful.

“We hope you all realize what a benefit collecting student work and encouraging creativity in the classroom can be,” said Josh.

Plosky said they couldn’t have described the project better.

“I also couldn’t help but realize that no one, when they’re taking MCAS, says they realized that their voice matters, that the freedom that they had in it allowed them to invest and exhibit their abilities and that they came away with a deeper understanding of themselves,” she added. “They said that – we didn’t put words in their mouths.”

In fact, Plosky said none of the students at the time even knew they were part of a pilot assessment program.

What’s next in the pilot?

Plosky said there was a lot of paperwork and time invested in the pilot. Thompson said in order to set the standards, teachers had to first collect a lot of student information and data and upload all of it including their work into a database.

“Then we went through a double-blind scoring process with those portfolios where other schools who participated in the pilot reviewed our student’s work, graded based off of the rubrics that they were provided for those tasks,” she said. “We did the same for the other schools, and then we went through and graded our own.”

Now the process is seeing how Winchester scores matched up to the other schools as well as how they match up to the student’s actual MCAS scores, Thompson said.

While the teachers are thrilled with how the project is going, Plosky said they still have a way to go. She said they’ve already made changes to the program and expect to make more, “so it’s a work in process.”

But she said it’s also been quite beneficial in that teachers already had excellent performance assessments in place and while they did some tweaking, those existing assessments fit naturally into the portfolio process.

“We also want to make sure that we’re anchored in a rigorous, authentic and equitable alternative to MCAS,” she added.

Lastly, Plosky said teachers also want to add the student voice to the process. They’d like students to chime in on the curation of assignments that would go into the portfolios as well as their reflection on what they learned.

“We’re still working on that. We’re still collecting information, and we’re still discussing which is what makes this a great part of this process, in that we don’t know exactly where it will end up,” she said. “We’re shaping it, and we’re working with other districts in order to have a voice and decide what could be an alternative to the MCAS. We’re not there yet, but we’re on our way.”