Table of Contents

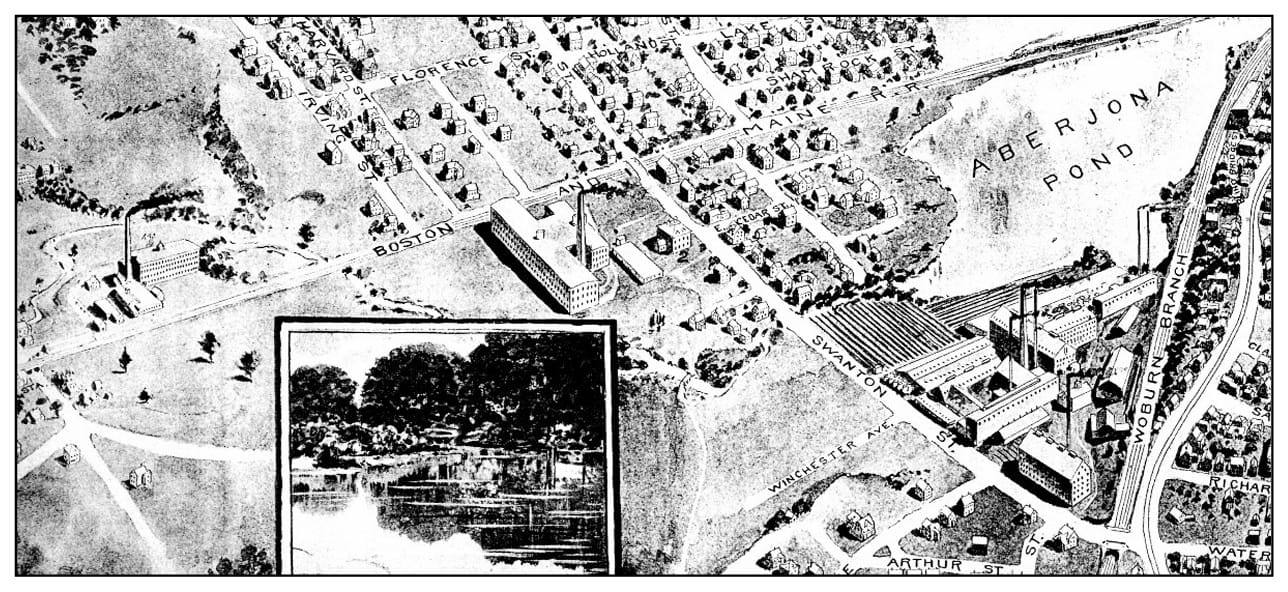

From Colonial times onward, the Aberjona River, running through town from Woburn down to the Mystic Lakes, offered a source of power for mills to operate in the area which became Winchester. The first industries were those essential to colonists, grist mills, sawmills, and a dye works.

As the leather business in Woburn boomed with the opening of the Middlesex Canal in 1803, South Woburn also contributed to that industry not only with tanneries but also with a mill producing tanning equipment.

With the advent of the railroad in 1835, offering transportation in the same general area as the river, Winchester developed even more as an industrial site. In addition to leather, products included furniture, sashes and blinds, cotton batting, piano cases, and felt. Early 20th century factories manufactured shoe fasteners and soda fountain works.

As more Boston professional men were making Winchester their home, a movement grew to move industry out of the town center and create a greenway beside the river through town. Although two major industries in the center were successfully removed, other factories continued operations south and north of the civic center into the mid-twentieth century. A mid-century planning effort to limit manufacturing to light industries and to a defined area succeeded, with the result that today the only industries are light and may only be found on the northern end of the town.

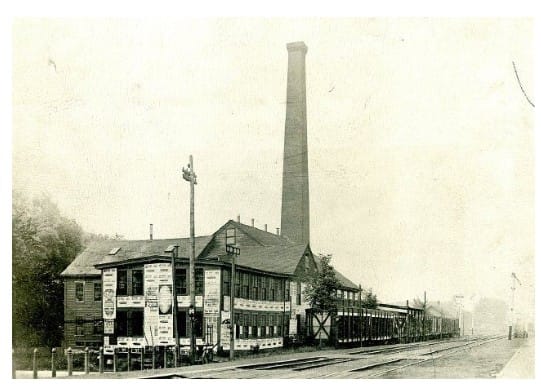

In the 19th century, Thompson Street was a route from Mr. Thompson’s home to his tannery, whose buildings and smoke stacks are visible in the background of this 19th-century photograph. The tannery played a vital part in the development of the commercial center but became a victim, at the end of the century, to changing conditions and a new society.

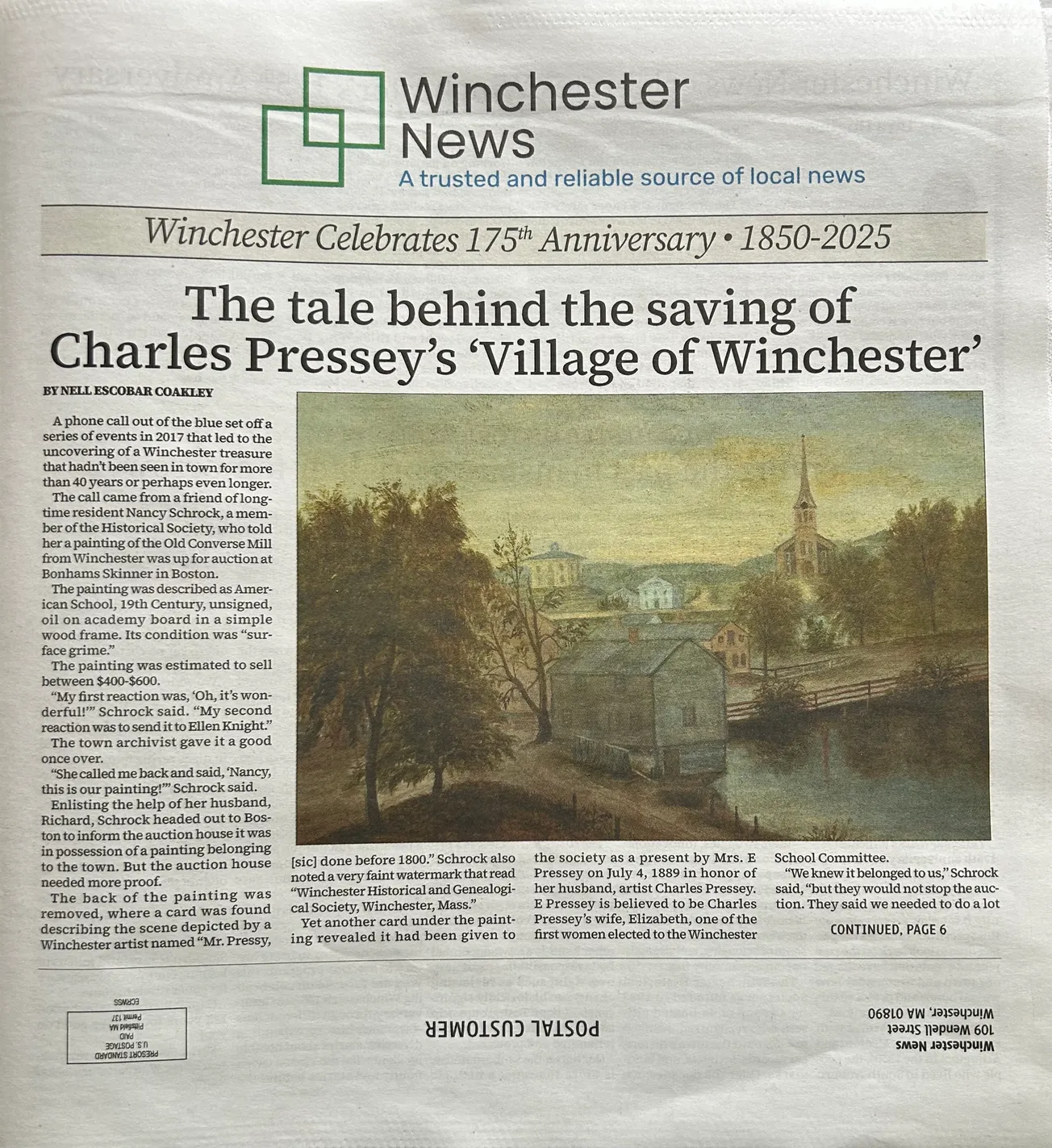

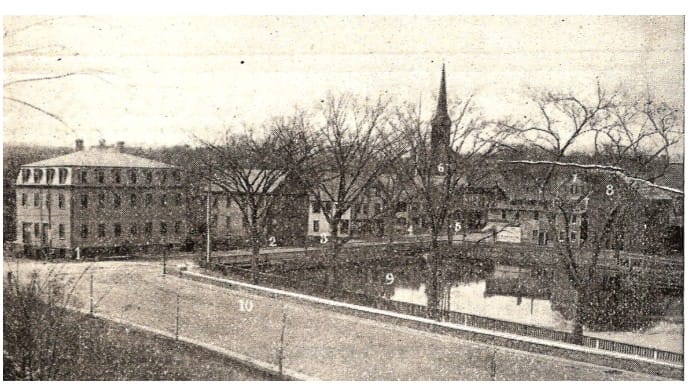

Edward Converse (1588-1663) was the first home builder, farmer, and miller within Winchester territory. Damming the river where today’s Main Street crosses over it, he created a mill pond which survives to this day, though successor mills ceased activity in 1909. In February 1641, a bridge was built, “Cold Bridge,” providing farmers access to the mill. The bridge today bears the name Converse.

To the south of Converse, Capt. William Symmes (1627-1691) put a dam across the Aberjona (near the bridge which now carries Mystic Valley Parkway across the river) and built a mill. His son William (1678-1764) had a mill at this spot and carried on the business of fulling and dyeing cloth. The Symmes dam stood until destroyed in 1864.

At the northern end of the river within Winchester territory, the Richardson family had a gristmill, referenced in a 1751 document. Jeduthan Richardson (1738-1815) relocated it in 1787 to what is now 620 Washington St. He did so after obtaining permission from the legislature to dig a canal to divert the waters of the river and get better power for the mill. The canal created an island in the river near the Woburn line which existed until the 1930s.

Mills were also built along Horn Pond Brook, the main tributary of the Aberjona River. Thomas Belknap (1670-1755), who moved to Woburn in 1698, bought 80 acres on land along what is now Main Street, running up to Horn Pond.

After building a dam and digging a canal, he put up a fulling mill and then a gristmill along the canal, near the foot of today’s Canal Street. He later acquired more land for a total of about 110 acres. His descendants added to the land, and the mills remained in the family through 1787. The site remained industrial through the early 20th century.

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

With not only the river to supply power but also the Middlesex Canal (opened 1803) and Boston and Lowell Railroad (opened 1835) providing transportation, South Woburn entered the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution, building new factories at old mill sites and at new locations.

Robert Bacon took over the site of the Symmes’ mill. Although a variety of products were made at the Bacon mills, ultimately the site was best known for the Bacon felt mills which operated in Winchester through 1951. The neighborhood was known as Baconville.

The Converse mill site was taken over by Abel Richardson, who built a new mill. Later the Whitney Machine Co. operated there until 1909. A laundry was also built next to the mill pond. The northern Richardson site was taken over for a lumber mill and later a watch-hand factory. In 1838, Benjamin F. Thompson built a tannery just south of the mill.

Along Horn Pond Brook, shortly before the town was incorporated Cowdery, Cobb & Nichols took over the Belknap site to make pianoforte cases until about 1895 when the factory began to produce felt. A patent leather factory became its neighbor in the early twentieth century. Also along the brook, during the first part of the 19th century, the Cutter family operated grist and lumber mills and gave their name to the Cutter Village area of Main Street where several in the family their homes. Furniture was a major product of their mills, under subsequent ownership.

At Lake Street, another tannery was built by the Blank Brothers about 1878. Alexander Mosely had yet another tannery, this one on Swanton Street, later owned by Beggs & Cobb.

The McKay Metallic Fastener Co. built a factory on vacant land near the river and north of Swanton Street in 1893. From at least 1854 through the 20th century, a tannery abutted the river south of Cross Street.

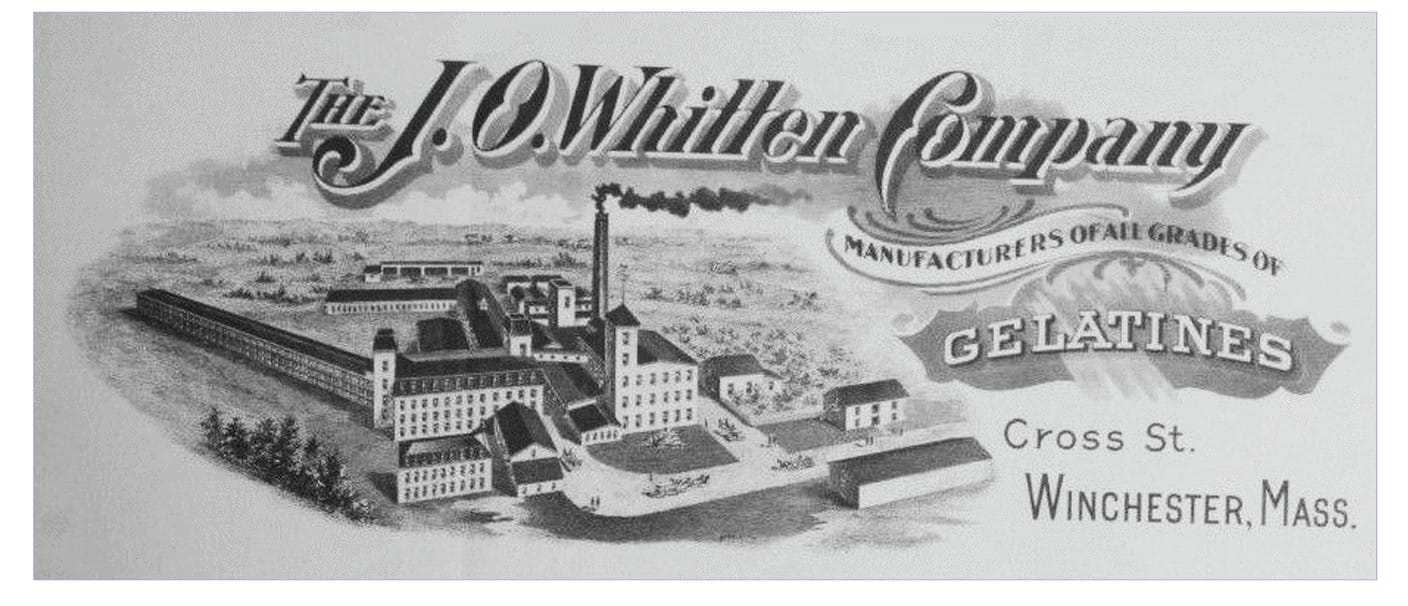

In 1902, the building was sold for the manufacture of gelatin. Across Leonard Pond from the gelatin factory, in 1915, a manufacturing plant for the Middlesex Japanning Company was built on Cross Street, next to Leonard Pond, later becoming the Allen H. McLatchy patent leather factory. In addition to the tanneries, in 1893 a factory for metallic shoe fasteners was also built along the Aberjona and, from 1903, was used for the manufacture of soda fountain works.

DEMISE OF HEAVY INDUSTRIES

From the 1890s through the 1910s, the solution for eliminating the foul water conditions was a combination of removing industry and creating parks. However, though industries were removed from Bacon Street to Main Street, the third phase of the river improvement program, coming after the advent of the Great Depression, left industry in place.

Further, other industries began operating on sites away from the river and brook. It took new measures from the Planning Board and Town Meeting to control what types of industries operated in town.

Surviving from the 19th into the early 20th centuries were the Bacon Felt Co., Eastern Felt Co., Whitney Machine Co., McKay/Puffer manufacturing, the McLatchy patent leather factory, Whitten gelatin factory, Beggs and Cobb tannery, and J .H. Winn’s sons. One large industry added was the Winchester Brick Company, which opened on East Street about 1920.

But one by one the large industries closed or moved away until only two were left after 1960. A movie theater opened in 1938 on the site of the Whitney Machine Company. The Puffer company went into receivership in 1939. After use by a trucking business, the Town purchased the site in 1944 for the town dump.

The Bacon Mill on Grove Place moved to Taunton in 1951, and the old building went up in flames in 1957. After the Beggs & Cobb company on Swanton Street moved its operations to Maine in 1957, a spectacular fire claimed that building in 1959. An enormous apartment house was approved in 1964 to be built on its site.

By 1960, the only two remaining large industries were the J. H. Winn Company on Washington Street and the Whitten Gelatin factory off Cross Street. The Whitten building also burned, in the second worst fire in town, only surpassed by Beggs & Cobb, in 1981. Its site was deemed too contaminated for residential use and was converted into soccer playing fields.

However, during the 20th century, new, smaller industries did come into town. No longer dependent on water power, they located away from the river and brook. For example, in the Waterfield Building on Waterfield Road in the Center were the Winslow Press and Hanlon Locomotive Sander Company, both there at the time of the 1945 fire. An apron factory occupied the former YMCA gym in the White Block on Mt. Vernon Street for some time.

New industries in the 20th century were not allowed to locate anywhere. In 1924, the first zoning map and bylaw for Winchester were adopted. These made it clear that industry would play a limited role in the town.

“Unobjectionable manufacturing” was confined essentially to an area abutting the river and railroad north of the town center. Unless a site was grandfathered, new buildings could not be constructed or existing buildings adapted for manufacturing such items as gelatin, glue, ammonia, chlorine, cement, rubber, metal, candles, dye, oil, paint, fireworks, fertilizer, linoleum, soap, polish, chewing tobacco, yeast, pickles, sauerkraut, and vinegar, nor could they be used for tanning, offal, refuse, iron smelting, sugar refining, and other uses.

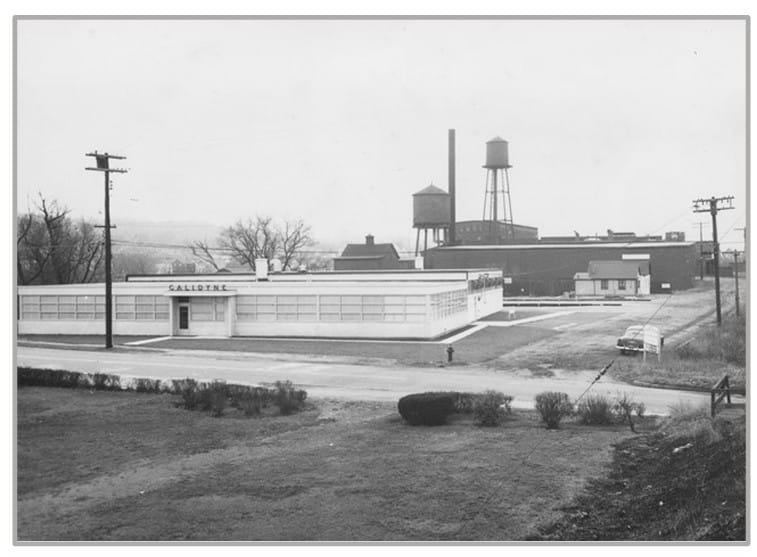

By the late 1950s, the Bylaw was considered inadequate to control industry in town. Concerned about the types and locations of industries in town, in spring 1959 Town Meeting created a Development and Industrial Commission for the promotion and development of the industrial resources of the town. It investigated available industrial land and advised on industrial opportunities.

When asked what kind of industry the commission was looking for, Chairman William C. Cusack replied, “Certainly not the old fashioned smoke stacks and rubbish heaps. We’re looking for modern, good-looking buildings that harmonize with the landscape and architecture of Winchester. We’re looking for low-cut buildings with shrubs and campus-type lawns.”

As a manifestation of its interest in light industry, in January 1960, the Board of Selectmen approved the creation of a 5.6-acre electronics park off Cross Street, known as the Parkway Electronics Park. Groundbreaking occurred in 1961 for the first building, leased to the Atlee Corp. of Woburn. Other businesses have included Dynamic Measurements Corp., developers of a line of data conversion products, and University Press.

In 1961, Town Meeting approved a Light Industrial Zone. As parcels were rezoned to that new zone, the old industrial zone eventually disappeared. The major available piece of industrial land in the 1960s was the Beggs & Cobb site. While the Commission advised and tried to facilitate industrial redevelopment, the parcel of 11-12 acres proved difficult to sell with existing zoning. After Town Meeting created an apartment zone in 1964, the site was purchased for the Parkview apartment building.

Otherwise, light industry did take hold in Winchester. By 1971, Winchester counted some 33 manufacturing firms. Still, debate continued about maintaining any kind of industry in town. In 1997, the Planning Board distributed a Triangle Master Plan for the area bounded on the east by Washington Street, on the north by the Woburn line, on the west by Sylvester Avenue/Middlesex Street, and on the south by the intersection of Skillings Road and Washington Street.

Regarding industrial use, the plan reported that less than half the land zoned for light industrial use was actually in industrial use (the zone allowing also for business uses). The Plan recommended that the zoning category be revised or replaced “to reflect a more modern office/research/high tech orientation rather than traditional industrial use. In fact, an industrial district, as currently described, may no longer be necessary.”

The Board further recommended that the light industrial district centered around River Street be designated for long-term residential use “so as to eventually remove this negative influence from the residential community.”

This change has not been enacted.

Dr. Ellen Knight, archivist for the Town of Winchester, is a local historian and journalist, as well as an independent scholar in Boston arts history.