Table of Contents

In Massachusetts, property tax overrides are generally governed by Proposition 2 ½, a state law (M.G.L. Ch. 59, § 21C) that limits the amount of revenue a municipality may raise from property taxes (limit is based on the total of all categories of real property and business owned personal property) each year to fund operation, excluding new growth (an increase in value due to renovation, new build or home sale).

This is the levy limit.

There is also a levy ceiling which equals 2 ½% of the municipality’s full and fair cash value (of real and personal property). Proposition 2 ½ does not limit the amount an individual’s tax bill may change from year to year.

This law was passed to insure that municipalities did not have unrestrained spending abilities without accountability to their residents. In order to increase the tax revenue above this limit, a town must pass either an override or an exclusion by a majority of voters at a town-wide election.

Overrides and exclusions were specifically made part of the law because when the law was passed, it was recognized that if inflation increased more than 2 ½% (or operational costs exceeded the 2 ½% levy limits) there would be a decline in the municipality’s spending ability.

There are three mechanisms for raising revenue beyond the 2.5% limit. One is an override and two are exclusions:

• An Operating Override: A permanent increase in the tax levy limit, allowing for an increase in the amount of property tax revenue a community may raise, in the year voted and future years, to fund recurring operational expenses (although it may be used for any spending purpose) such as municipal services or school staff.

A specified amount for the increase is decided by the Select Board and their majority vote is needed to place the override question on the ballot for town-wide vote. A majority of the town-wide vote is required to pass the override.

Town Meeting is responsible for appropriating the funds. The total override amount does not need to be added to the budget in year one, but can be spread out over a number of years to ease the burden on property tax bills.

The new levy limit, including the override, cannot exceed the levy ceiling. However, the increase in the municipality’s levy limit becomes part of the base for calculating future years’ levy limits, thereby resulting in a permanent increase in taxing authority.

There are two kinds of exclusion overrides, both raise the levy for capital spending only.

• Debt Exclusion: A temporary increase in the tax levy to cover the expense of a major capital project (to cover the cost of the loan or bond), like the new Lynch Elementary School.

This levy increase expires once the debt is paid, which is typically between 5-20 years. So it lasts for the life of the borrowing.

The Select Board would once again vote, this time a ⅔ vote is needed, to place the override on the ballot specifying the amount of the debt exclusion.

It again requires a majority in the town-wide vote to pass. It is up to Town Meeting to appropriate the related override funds to the borrowing.

• Capital Expenditure Exclusion (also known as Capital Exclusion): Also a temporary levy increase for a specific capital purchase or project. This levy increase lasts for one year and has the same process as the debt exclusion.

Exclusions are temporary because they do not actually become a part of the levy limit so they do not increase the base for calculating future years’ limits. Exclusions are raised outside the levy limit. They only increase the maximum amount communities can levy for the temporary period of time. The exclusions are the only way a municipality can levy above the community’s levy limit and levy ceiling.

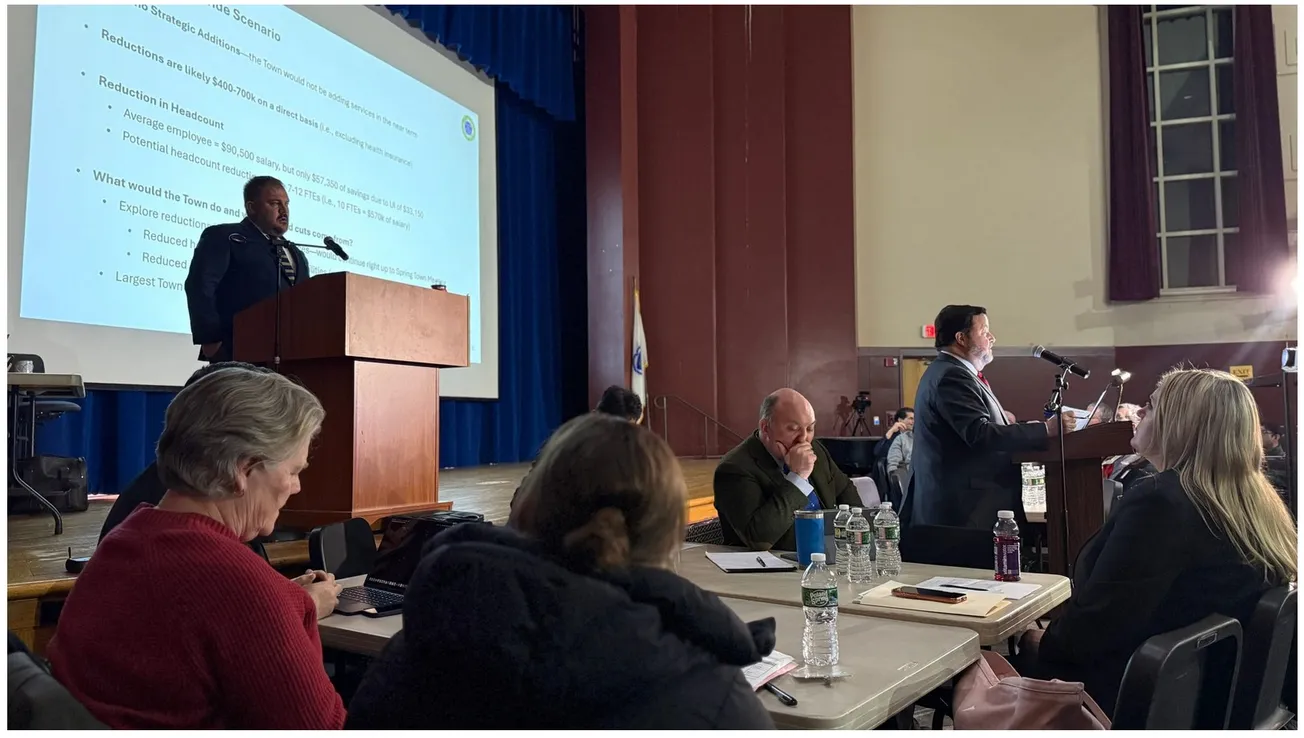

The State of the Town Committee recently issued a report which currently forecasts a structural deficit causing the recommendation of an override vote on the March 21, 2026 town election ballot.

The override on the March ballot will be an Operating Override which will fund operating expenses and stabilization funds to support both operating and capital needs. The structural deficit is due to the fact that expenses are out pacing revenue in town.

Winchester relies heavily on property tax revenue (Winchester is +95% residential) to fund its budget and capital expenses. The operating deficit is currently around $5 million, which could continue to grow, according to the State of the Town Committee.

There is also a backlog of capital needs of around $54 million.

The town is concerned that if a drawdown over years of the town’s reserves to below 10% (currently around 18%) is required to fund rising costs, it could jeopardize the town’s Moody’s AAA bond rating (which has been currently given to only 14 communities out of 351 in Massachusetts).

A poorer bond rating increases the cost of borrowing for the community (due to increased interest rates based on higher risk).

The final amount, if any, of the requested override (to be split between operations and capital) to appear on the ballot will be decided by Feb. 14 and is currently in the $12.5 to $15 million range.

To view the report from the State of the Town Committee, click here. Presentation slides from the State of the Town Update can be found here. Readers will find tax implications and tax fairness programs and potential exceptions on the slides. To learn more about Proposition 2 ½ look here.

Editors note: This article has been updated for clarity and to correct that only an Operational Override will appear on the March 21 ballot.

Tara Hughes is the president of the Winchester News Board of Directors. She is a lawyer, who served on Town Meeting for several years.

Have you got any ideas for our DO YOU KNOW segment? If so, email editor@winchesternews.org with the subject line DO YOU KNOW.